- Home

- Mrs. Molesworth

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Read online

GRANDMOTHER DEAR

A Book for Boys and Girls

by

MRS. MOLESWORTH

Author of 'Carrots,' 'Cuckoo Clock,' 'Tell Me a Story'

Illustrated by Walter Crane

MacMillan and Co., LimitedSt. Martin's Street, London1932First Edition November 1878. Reprinted December 1878September and December 1882, 18861887, 1889, 1892, 1895, 1897, 1899, 1900, 1902, 1904, 1906, 1909, 19111918, 1920, 1932

Printed in Great Britainby R. & R. Clark, Limited, Edinburgh

'I HOPE IT ISN'T HAUNTED.']

TO

_OUR_ 'GRANDMOTHER DEAR,'

A. J. S.

Maison Du Chanoine,_October_ 1878.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. Making Friends

CHAPTER II. Lost in the Louvre

CHAPTER III. "_Where_ is Sylvia?"

CHAPTER IV. The Six Pinless Brooches

CHAPTER V. Molly's Plan

CHAPTER VI. The Apple-Tree of Stefanos

CHAPTER VII. Grandmother's Grandmother

CHAPTER VIII. Grandmother's Story (_Continued_)

CHAPTER IX. Ralph's Confidence

CHAPTER X. "That Cad Sawyer"

CHAPTER XI. "That Cad Sawyer"--Part II.

CHAPTER XII. A Christmas Adventure

CHAPTER XIII. A Christmas Adventure--Part II.

CHAPTER XIV. How this Book came to be written

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

Sylvia lost in the Louvre

"Whose Drawer is this?"

Under the Apple-Tree

"Zwanzig--Twenty Schelling, that Cup"

In the Coppice

"Good-Bye again, my Boy, and God bless you!"

"I hope it isn't Haunted"

CHAPTER I.

MAKING FRIENDS.

"Good onset bodes good end." SPENSER.

"Well?" said Ralph.

"Well?" said Sylvia.

"Well?" said Molly.

Then they all three stood and looked at each other. Each had his or herown opinion on the subject which was uppermost in their minds, but eachwas equally reluctant to express it, till that of the others had been gotat. So each of the three said "Well?" to the other two, and stoodwaiting, as if they were playing the old game of "Who speaks first?" Itgot tiresome, however, after a bit, and Molly, whose patience was themost quickly exhausted, at last threw caution and dignity to the winds.

"Well," she began, but the "well" this time had quite a different tonefrom the last; "_well_," she repeated emphatically, "I'm the youngest,and I suppose you'll say I shouldn't give my opinion first, but I justwill, for all that. And my opinion is, that she's just as nice as she canbe."

"And I think so too," said Sylvia, "Don't you, Ralph?"

"I?" said Ralph loftily, "you forget. _I_ have seen her before."

"Yes, but not to _remember_," said Sylvia and Molly at once. "You mightjust as well never have seen her before as far as that goes. But isn'tshe nice?"

"Ye-es," said Ralph. "I don't think she's bad for a grandmother."

"'For a grandmother!'" cried Molly indignantly. "What do you mean, Ralph?What can be nicer than a nice grandmother?"

"But suppose she wasn't nice? she needn't be, you know. There aregrandmothers and grandmothers," persisted Ralph.

"Of course I know _that_," said Molly. "You don't suppose I thought ourgrandmother was everybody's grandmother, you silly boy. What I say isshe's just like a real grandmother--not like Nora Leslie's, who is alwaysscolding Nora's mother for spoiling her children, and wears such grand,quite _young lady_ dresses, and has _black_ hair," with an accent ofprofound disgust, "not nice, beautiful, soft, silver hair, like _our_grandmother's. Now, isn't it true, Sylvia, isn't our grandmother justlike a _real_ one?"

Sylvia smiled. "Yes, exactly," she replied. "She would almost do for afairy godmother, if only she had a stick with a gold knob."

"Only perhaps she'd beat us with it," said Ralph.

"Oh no, not _beat_ us," cried Molly, dancing about. "It would be worsethan that. If we were naughty she'd point it at us, and then we'd allthree turn into toads, or frogs, or white mice. Oh, just fancy! I am soglad she hasn't got a gold-headed stick."

"Children," said a voice at the door, which made them all jump, though itwas such a kind, cheery voice. "Aren't you ready for tea? I'm glad to seeyou are not very tired, but you must be hungry. Remember that you'vetravelled a good way to-day."

"Only from London, grandmother dear," said Molly; "that isn't very far."

"And the day after to-morrow you have to travel a long way farther,"continued her grandmother. "You must get early to bed, and keepyourselves fresh for all that is before you. Aunty says _she_ is veryhungry, so you little people must be so too. Yes, dears, you may rundownstairs first, and I'll come quietly after you; I am not so young asI have been, you know."

Molly looked up with some puzzle in her eyes at this.

"Not so young as you have been, grandmother dear?" she repeated.

"Of course not," said Ralph. "And you're not either, Molly. Once you werea baby in long clothes, and, barring the long clothes, I don't know butwhat----"

"Hush, Ralph. Don't begin teasing her," said Sylvia in a low voice, notlost, however, upon grandmother.

What _was_ lost upon grandmother?

"And what were you all so busy chattering about when I interrupted youjust now?" she inquired, when they were all seated round the tea-table,and thanks to the nice cold chicken and ham, and rolls and butter andtea-cakes, and all manner of good things, the children fast "losing theirappetites."

Sylvia blushed and looked at Ralph; Ralph grew much interested inthe grounds at the bottom of his tea-cup; only Molly, Molly theirrepressible, looked up briskly.

"Oh, nothing," she replied; "at least nothing particular."

"Dear me! how odd that you should all three have been talking at onceabout anything so uninteresting as nothing particular," said grandmother,in a tone which made them all laugh.

"It wasn't _exactly_ about nothing particular," said Molly: "it was about_you_, grandmother dear."

"Molly!" said Sylvia reproachfully, but Molly was not so easily to besnubbed.

"We were wishing," she continued, "that you had a gold-headed stick, andthen you'd be quite _perfect_."

It was grandmother's and aunty's turn to laugh now.

"Only," Molly went on, "Ralph said perhaps you'd beat us with it, andI said no, most likely you'd turn us into frogs or mice, you know."

"'Frogs or mice, I know,' but indeed I don't know," said grandmother;"why should I wish to turn my boy and girl children into frogs and mice?"

"If we were naughty, I meant," said Molly. "Oh, Sylvia, you explain--Ialways say things the wrong way."

"It was I that said you looked like a fairy godmother," said Sylvia,blushing furiously, "and that put it into Molly's head about the frogsand mice."

"But the only fairy godmother _I_ remember that did these wonderfulthings turned mice into horses to please her god-daughter. Have you notgot hold of the wrong end of the story, Molly?" said grandmother.

"The wrong end and beginning and middle too, I should say," observedRalph.

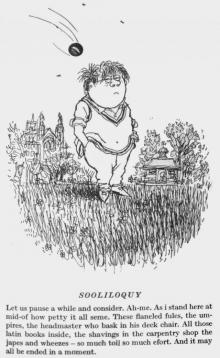

"Yes, grandmother dear, I always do," said Molly, complacently. "I neverremember stories or anything the right way, my head is so funnily made."

"When you can't find your gloves, because you didn't put them awaycarefully, is it the fault of the shape of the chest of drawers?"inquired grandmother quietly.

"Yes, I suppose so,--at least, no, I mean, of course it isn't," repliedMolly, taking heed to her words half-way through, when she saw that theywere all laughing at her.

Grandmother smiled, but said no more.

"What a wool-gathering little brain it is," she said to herself.

When she smiled, all the children agreed together afterwards, she lookedmore like a fairy godmother than ever. She was really a _very_ pretty oldlady. Never very tall, with age she had grown smaller, though stillupright as a dart; the "November roses" in her cheeks were of their kindas sweet as the June ones that nestled there long ago--ah! so long agonow; and the look in her eyes had a tenderness and depth which can onlycome from a life of unselfishness, of joy and much sorrow too--a lifewhose lessons have been well and dutifully learnt, and of which none hasbeen more thoroughly taken home than that of gentle judgment of, and muchpatience with, others.

While they are all finishing their tea, would you, my boy and girlfriends, like to know who they were--these three, Ralph, Sylvia, andMolly, whom I want to tell you about, and whom I hope you will love? WhenI was a little girl I liked to know exactly about the children in mybooks, each of whom had his or her distinct place in my affections. Iliked to know their names, their ages, all about their homes and theirrelations _most_ exactly, and more than once I was laughed at for writingout a sort of genealogical tree of some of my little fancy friends'family connections. We need not go quite so far as _that_, but I willexplain to you about these new little friends of yours enough for you tobe able to find out the rest for yourselves.

They had never seen their grandmother before, never, that is to say, inthe girls' case, and in Ralph's "not to remember her." Ralph was fourteennow, Sylvia thirteen, and Molly about a year and a half younger. Morethan seven years ago their mother had died, and since then they had beenliving with their father, whose profession obliged him often to changehis home, in various different places. It had been impossible for theirgrandmother, much as she wished it, to have had them hitherto with her,for, for several years out of the seven, her hands, and those of aunty,too, her only other daughter besides their mother, had been more thanfilled with other cares. Their grandfather had been ill for many yearsbefore his death, and for his sake grandmother and aunty had left theEnglish home they loved so much, and gone to live in the south of France.And after his death, as often happens with people no longer young, andsomewhat wearied, grandmother found that the old dream of returning"home," and ending her days with her children and old friends round her,had grown to be but a dream, and, what was more, had lost its charm. Shehad grown to love her new home, endeared now by so many associations; shehad got used to the ways of the people, and felt as if English ways wouldbe strange to her, and as aunty's only idea of happiness was to find itin hers, the mother and daughter had decided to make their home where fornearly fourteen years it had been. They had gone to England this autumnfor a few weeks, finally to arrange some matters that had been leftunsettled, and while there something happened which made them very gladthat they had done so. Mr. Heriott, the children's father, had receivedan appointment in India, which would take him there for two or threeyears, and though grandmother and aunty were sorry to think of his goingso far away, they were--oh, I can't tell you how delighted! when heagreed to their proposal, that the children's home for the time should bewith them. It would be an advantage for the girls' French, saidgrandmother, and would do Ralph no harm for a year or two, and if hisfather's absence lasted longer, it could easily be arranged for him tobe sent back to England to school, still spending his holidays at Chalet.So all was settled; and grandmother, who had taken a little house atDover for a few weeks, stayed there quietly, while aunty journeyed awayup to the north of England to fetch the children, their father being toobusy with preparations for his own departure to be able convenientlyto take them to Dover himself. There were some tears shed at parting with"papa," for the children loved him truly, and believed in his love forthem, quiet and undemonstrative though his manner was. There were sometears, too, shed at parting with "nurse," who, having conscientiouslyspoilt them all, was now getting past work, and was to retire to hermarried daughter's; there were a good many bestowed on the rough coat ofShag, the pony, and the still rougher of Fusser, the Scotch terrier; butafter all, children are children, and for my part I should be very sorryfor them to be anything else, and the delights of the change and thebustle of the journey soon drowned all melancholy thoughts.

And so far all had gone charmingly. Aunty had proved to be all that couldbe wished of aunty-kind, and grandmother promised more than fairly.

"What _would_ we have done if she had been very tall and stout, andfierce-looking, with spectacles and a hookey nose?" thought Molly, and asthe thought struck her, she left off eating, and sat with wide open eyes,staring at her grandmother.

Though grandmother did not in general wear spectacles--only when readingvery small print, or busied with some peculiarly fine fancywork--nothingever seemed to escape her notice.

"Molly, my dear, what are you staring at so? Is my cap crooked?" shesaid. Molly started.

"Oh no, grandmother dear," she replied. "I was only thinking----" shestopped short, jumped off her seat, and in another moment was round thetable with a rush, which would have been sadly trying to mostgrandmothers and aunties, only fortunately these special ones were notlike most!

"What is the matter, dear?" grandmother was beginning to exclaim, whenshe was stopped by feeling two arms hugging her tightly, and a ratherbread-and-buttery little mouth kissing her valorously.

"Nothing's the matter," said Molly, when she stopped her kisses, "it onlyjust came into my head when I was looking at you, how nice you were, youdear little grandmother, and I thought I'd like to kiss you. I don't wantyou to have a gold-headed stick, but I do want one thing, and then you_would_ be quite perfect. Oh, grandmother dear," she went on, claspingher hands in entreaty, "just tell me this, _do_ you ever tell stories?"

Grandmother shook her head solemnly. "I _hope_ not, my dear child," shesaid, but Molly detected the fun through the solemnity. She gave awriggle.

"Now you're laughing at me," she said. "You _know_ I don't mean thatkind. I mean do you ever tell real stories--not real, I don't mean, forvery often the nicest aren't real, about fairies, you know--but you knowthe sort of stories I mean. You would look so beautiful telling stories,wouldn't she now, Sylvia?"

"And the stories would be beautiful if I told them--eh, Molly?"

"Yes, I am sure they would be. _Will_ you think of some?"

"We'll see," said grandmother. "Anyway there's no time for stories atpresent. You have ever so much to think of with all the travelling thatis before you. Wait till we get to Chalet, and then we'll see."

"I like _your_ 'we'll see,'" said Molly. "Some people's 'we'll see,' justmeans, 'I can't be troubled,' or, 'don't bother.' But I think _your_'we'll see' sounds nice, grandmother dear."

"I am glad you think so, grand-daughter dear; and now, what about goingto bed? It is only seven, but if you are tired?"

"But we are not a bit tired," said Molly.

"We never go to bed till half-past eight, and Ralph at nine," saidSylvia.

The word "bed" had started a new flow of ideas in Molly's brain.

"Grandmother," she said, growing all at once very grave, "that reminds meof one thing I wanted to ask you; do the tops of the beds ever come downnow in Paris?"

"'Do the tops of the beds in Paris ever come down?'" repeatedgrandmother. "My dear child, what _do_ you mean?"

"It was a story she heard," began Sylvia, in explanation.

"About somebody being suffocated in Paris by the top of the bed comingdown," continued Ralph.

"It was robbers that wanted to steal his money," added Molly.

Grandmother began to look less mystified. "Oh, _that_ old story!" shesaid. "But how did you hear it? I remember it when I was a little girl;it really happened to a friend of my grandfather's, and afterwards I cameacross it in a little book about dogs. 'Fidelity of dogs,' was the nameof it, I think. The dog saved the traveller's life by dragging him out ofthe bed."

"Yes," said aunty, "I remember that book t

oo. It was among your oldchild's books, mother. A queer little musty brown volume, and I rememberhow the story frightened me."

"There now!" said Molly triumphantly. "You see it frightened aunty too.So I'm _not_ such a baby after all."

"Yes, you are," said Ralph. "People might be frightened without makingsuch a fuss. Molly declared she would rather not go to Paris at all._That's_ what I call being babyish--it isn't the feeling frightenedthat's babyish--for people might feel frightened and still _be_ brave,mightn't they, grandmother?"

"Certainly, my boy. That is what _moral_ courage means."

"Oh!" said Molly, as if a new idea had dawned upon her. "I see. Then itdoesn't matter if I am frightened if I don't tell any one."

"Not exactly that," said grandmother. "I would _like_ you all to bestrong and sensible, and to have good nerves, which it would take a gooddeal to startle, as well as to have what certainly is best of all, plentyof moral courage."

"And if Molly is frightened, she certainly couldn't help telling," saidSylvia, laughing. "She does _so_ pinch whoever is next her."

"There was nothing about a dog in the story of the bed we heard," saidMolly. "It was in a book that a boy at school lent Ralph. I wouldn't everbe frightened if I had Fusser, I don't think. I do so wish I had askedpapa to let him come with us--just _in case_, you know, of the bedshaving anything funny about them: it would be so comfortable to haveFusser."

At this they all laughed, and aunty promised that if Molly feltdissatisfied with the appearance of her bed, she would exchange with her.And not long after, Sylvia and Molly began to look so sleepy, in spite oftheir protestations that the dustman's cart was nowhere near _their_door, that aunty insisted they must be mistaken, _she_ had heard hiswarning bell ringing some minutes ago. So the two little sisters cameround to say good-night.

"Good night, grandmother dear," said Molly, in a voice which tried hardto be brisk as usual through the sleepiness.

Grandmother laid her hand on her shoulder and looked into her eyes. Mollyhad nice eyes when you looked at them closely: they were honest andcandid, though of too pale a blue to show at first sight the expressionthey really contained. Just now too, they were blinking and winking alittle. Still grandmother must have been able to read in them what shewanted, for her face looked satisfied when she withdrew her gaze.

"So I am _really_ to be 'grandmother dear,' to you, my dear funny littlegirl?" she said.

"Of course, grandmother dear. Really, _really_ I mean," said Molly,laughing at herself. "Do you see it in my eyes?"

"Yes, I think I do. You have nice honest eyes, my little girl."

Molly flushed a little with pleasure. "I thought they were rather ugly.Ralph calls them 'cats',' and 'boiled gooseberries,'" she said. "AnywaySylvia's are much prettier. She has such nice long eyelashes."

"Sylvia's are very sweet," said grandmother, kissing her in turn, "and wewon't make comparisons. Both pairs of eyes will do very well my darlings,if always

'The light within them, Tender is and true.'

Now good night, and God bless my little grand-daughters. Ralph, you'll situp with me a little longer, won't you?"

"What nice funny things grandmother says, doesn't she, Sylvia?" saidMolly, as they were undressing.

"She says nice things," said Sylvia, "I don't know about they're beingfunny. You call everything funny, Molly."

"Except you when you're going to bed, for then you're very often rathercross," said Molly.

But as she was only _in fun_, Sylvia took it in good part, and, afterkissing each other good night, both little sisters fell asleep withoutloss of time.

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories

An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car

Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car The Children of the Castle

The Children of the Castle The Magic Nuts

The Magic Nuts Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Silverthorns

Silverthorns The Third Miss St Quentin

The Third Miss St Quentin Christmas-Tree Land

Christmas-Tree Land Philippa

Philippa Jasper

Jasper The Little Old Portrait

The Little Old Portrait Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Us, An Old Fashioned Story

Us, An Old Fashioned Story The Constant Prince

The Constant Prince Blanche: A Story for Girls

Blanche: A Story for Girls The Cuckoo Clock

The Cuckoo Clock The Carved Lions

The Carved Lions Tell Me a Story

Tell Me a Story That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie

That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie Sweet Content

Sweet Content Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories

The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball

Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball Nurse Heatherdale's Story

Nurse Heatherdale's Story Adventures of Herr Baby

Adventures of Herr Baby Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver

Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories

Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy

Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy