- Home

- Mrs. Molesworth

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children Page 10

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children Read online

Page 10

CHAPTER X.

TOM'S SORE THROAT.

"Plenty of jelly and nice things to eat, And we'll hope he'll be better to-morrow."

I woke very early the next morning. I woke with that queer feeling thateverybody knows, of something having happened. And before I was awakeenough in my mind even to get a distinct thought of what it was that hadhappened, I yet had a feeling that it was something pleasant. For thefirst time since mother had gone I woke without that terrible feeling ofloneliness that had been getting worse and worse every day.

As usual I glanced over at Tom's bed to see if he was still asleep.

"Tom," I said softly, "are you awake?"

"Yes," said Tom, all in a minute, as if he had been awake some time.

It was all clear in my head now--about our losing our way and findingMiss Goldy-hair and the letter to Pierson, and Miss Goldy-hair,promising to invite us to go and see her, and everything.

"Tom," I said, "we can't go to Pierson now. I gave her leave to tell."

"Who?" said Tom, "Pierson?"

"No," I replied. "Of course not. What would be the sense of writing asecret to Pierson if she was to tell it?"

"I didn't know you wrote a secret to Pierson," said Tom; "I can'tunderstand."

He spoke very meekly, but I felt provoked with him. I felt anxious andfidgety, even though I was so pleased about having found MissGoldy-hair; and I thought Tom didn't seem to care enough.

"How stupid you are, Tom," I said. "You knew I had written to Pierson totell her I was going to take you and Racey to her."

"I didn't know it until I heard you tell _her_," said Tom. "I don'tthink we _could_ go to Pierson's, Audrey. We might get lost again."

"We wouldn't get lost," I said. "We wouldn't get lost in a cab and inthe railway. You're so stupid, Tom. You've been going on so about beingso unhappy here, and it was all to please you I thought of going toPierson's, and now I suppose you'll make out it was all me, when UncleGeoff speaks about it."

"I never said it was all you," said Tom, "but I thought you'd be sopleased about Miss Goldy-hair; and now you're quite vexed with me."

We were on the fair way to a quarrel, when a distraction came from thedirection of Racey.

"Her's got a' air-garden," he called out suddenly in his little shrillvoice. "Did you know her had a' air-garden? I've been d'eaming about it.Her's going to show it me. It's full of fairies." (He really said"wairies," but I can't write all his speaking like that; it would be sodifficult for you to understand.)

We couldn't help laughing at Racey's fancies, and in his turn Racey wasa little inclined to be offended, so Tom and I joined together to try tobring him round.

"I don't know how it is we've got in the way of being so cross to eachother," I said sadly. "I'm sure it's quite time Miss Goldy-hair orsomebody should teach us how to be good again. How dreadfully quick oneforgets."

"Miss Goldy-hair wouldn't like us if we quarrelled," said Tom in amelancholy voice.

"Her wouldn't _whip_ us," observed Racey.

"No, she would try to teach us to be good," I said. "I'm sure I'd try tobe good if I was with her. Tom," I went on--and here I really must putdown what I said, whether it vexes somebody or not--"Tom, do you know, Ithink her face is just exactly like an angel's when you look at it quiteclose."

"Or a fairy's," said Tom.

"No," I said, "an angel's. Fairies are more merry looking than she is.She has such a kind, sorry look--that's why I think her face is like anangel's."

Tom gave a great sigh.

"What's the matter, Tom?" I said.

"I don't know. I think I've got a headache," said Tom.

"But aren't you glad Miss Goldy-hair's coming to fetch us?" I said in myturn.

"Kite early," said Racey.

"Yes, quite early. She promised," I said. "Aren't you glad, Tom?"

"Yes," said Tom, "but I'm sleepy."

I began to be afraid that he was not quite well. Perhaps it was withbeing so frightened and crying so the night before. I made Racey bequite still, and I didn't speak any more, and in a little I heard byTom's breathing that he had gone to sleep again. He was still asleepwhen Sarah came up-stairs to dress us, and I was rather glad, for therewere several things I wanted to ask her. Mrs. Partridge had come back,she told me, but much later than she had expected, for she had missedher train and got her best bonnet spoilt walking to the station, and shewas very cross.

"But she doesn't know anything about us being out last night?" I said toSarah.

"Of course not, Miss Audrey. It isn't likely as _I_'d tell her. But Ican't think why you didn't ask me to post your letter instead ofthinking of going off like that yourselves. I'll never forget to thelast day of my life how frightened I was when I couldn't find you."

"I didn't want to ask you to post it, because I thought perhaps Mrs.Partridge would find out, and then she'd scold you," I said.

Sarah looked mollified.

"Scoldings don't do much good to anybody, it seems to me," she remarked."I hope your uncle won't scold you," she added. "He was a good while atthat lady's last night, but I shouldn't think she's one to makemischief."

"Did he go last night?" I asked, rather anxiously.

"Yes, Miss Audrey. I gave him the card, and he went off at once.Benjamin"--that was Uncle Geoff's footman--"Benjamin says she's a younglady whose mother died not long ago. He knows where she lives and all,but I didn't remember her--not opening the door often you see. She's avery nice young lady, but counted rather odd-like in her ways. For allshe's so rich she's as plain as plain in her dress, and for ever workingaway among poor children, and that sort of way. But to be sure she'salone in the world, and when people are that, and so rich too, it's wellwhen they give a thought to others."

Here a little shrill voice came from the corner of the room, where Raceywas still in his cot.

"What's 'alone in the world'?" he inquired.

Sarah gave a little start.

"Bless me," she said, "I thought he was still asleep. Never mind, MasterRacey," she said, turning to him, "you couldn't understand."

Racey muttered to himself at this. He hated being told he couldn'tunderstand. But just then Tom woke. He said his headache was better, butstill I didn't think he looked quite well.

"Is the new nurse coming to-day?" he inquired of Sarah. Sarah shook herhead.

"I've heard nothing about her," she said. "I don't think Mrs. Partridgecan have settled anything, and perhaps that's why she came home socross."

"I don't care if her comes or if her doesn't," said Racey, who had grownvery brave. "_I_'m going to Miss Goldy-hair's."

Sarah wasn't in the room just then, and I was rather glad of it. SomehowI wouldn't have liked her to hear our name for the young lady, and Itold him he wasn't to say it to anybody but Tom and me--perhaps theyoung lady wouldn't like it.

Racey said nothing, but I noticed he didn't say it again before Sarah.He was a queer little boy in some ways. When you thought he wasn'tnoticing a thing he'd know it quite well, and then he'd say it out againsome time when you didn't want him to, very likely.

All breakfast time I kept wondering what was going to happen. Would theyoung lady come for us herself? Would she send to ask Uncle Geoff to letus go, or had she asked him already? Tom was very quiet--he didn't seemvery hungry, though he said his headache was better, but his eyes lookedheavy.

"I wish she'd come," he said two or three times. "I'd like to sit on herknee and for her to tell us stories. I'd like to sit on somebody's knee.You're not big enough, are you, Audrey?"

I was afraid not, but I did my best. I sat down on a buffet leaningagainst a chair, and made the best place I could for Tom.

"Is your head bad again, Tom?" I asked.

"No, only I like sitting this way--quite still," he replied.

I couldn't help being afraid that he was ill. The thought made me veryunhappy, for it was my fault that he had gone out in the wet and thecold the night before, and I began to see that I had not been ta

kingcare of my little brothers in the right way, and that mother would bevery sorry if she knew all about it. It made me feel gentler anddifferent somehow, and I thought to myself that I would ask MissGoldy-hair to tell me how I could know better what was the right way. Iwas just thinking that, and I think one or two tears had dropped onTom's dark hair, when the door opened and Uncle Geoff came in.

At first I couldn't help being frightened. Miss Goldy-hair was sure tohave told him, and however nicely she had told him I didn't see how itwas _possible_ he shouldn't be angry. I looked up at him, and the tearsbegan to come quicker, and I had to hold my breath to keep myself frombursting out into regular crying. To my surprise Uncle Geoff knelt downon the floor beside me and stroked my head very kindly.

"My poor little Audrey," he said, "and you have been unhappy since youcame here? I am so sorry that I have not been able to make you happy,but it isn't too late yet to try again, is it?"

I was so surprised that I couldn't speak. I just sat still, holding Tomclose in my arms, and the tears dropping faster and faster.

"I thought you thought I was so naughty, Uncle Geoff," I said at last."Mrs. Partridge said so, and she said we were such a trouble to you. Ithought you'd be glad if we went away; and I thought we _were_ gettingnaughty. We never quarrelled hardly at home."

"But at home you had your mother and your father, who understood how tokeep you happy, so that you weren't tempted to quarrel," said UncleGeoff. "And I'm only a stupid old uncle, who needs teaching himself, yousee. Let's make a compact, Audrey. If you are unhappy, come and tell meyourself, and we'll see if we can't put it right. Never mind what Mrs.Partridge says. She means to be kind, but she's old, and it's a verylong time since she had to do with children. Now will you promise methis, Audrey?"

"Yes, Uncle Geoff," I said, in a very low voice.

"And you will never think of running away from your cross old uncleagain, will you?" he said.

"No, Uncle Geoff," I replied. "I didn't mean to be naughty. I _really_didn't. But we did think nobody cared for us here, and mother told meto make the boys happy."

"And we will make them happy. We'll begin to-day and see if we can'tmanage to understand each other better," said Uncle Geoff, cheerfully."_To-day_ you will be happy any way, I think, for I have got aninvitation for you. You know whom it's from?"

"Yes," said Tom and I together. Tom, who had been lying quite still inmy arms all this time listening half sleepily, started up in excitement."Yes," we said, "it's from Miss Goldy-hair."

"Miss--how much?" said Uncle Geoff.

We couldn't help laughing.

"We called her that because we didn't know her name, and her hair was sopretty," we said.

Uncle Geoff laughed too.

"It's rather a nice name, I think," he said. "What funny creatureschildren are! I must set to work to understand them better. Well, yes,you're quite right. Miss Goldy-hair wants you all three to go and spendall the day with her. But what's the matter with Tom?" he went on. "Haveyou a headache, my boy?" for Tom had let his head drop down again on myshoulder.

"Yes," said Tom, "and a sore t'roat, Uncle Geoff." Uncle Geoff lookedrather grave at this.

"Let's have a look at you, my boy," he said.

He lifted Tom up in his arms and carried him to the window and examinedhis throat.

"He must have caught cold," he said. "It isn't very bad so far, but I'mafraid--I'm very much afraid he mustn't go out to-day."

He--Uncle Geoff--looked at me as if he were wondering how I would takethis.

"Oh, poor Tom!" I cried. "Oh, Uncle Geoff, it was all my fault forletting him go out last night. Oh, Uncle Geoff, do forgive me. I'll beso good, and I'll try to amuse poor Tom and make him happy all day."

"Then you don't want to go without him?" said Uncle Geoff.

"Oh, _of course_ not," I replied. "Of course I'd not leave Tom when he'sill, and when it was my fault too. Oh, Uncle Geoff, you don't think he'sgoing to be very ill, do you?"

Tom looked up very pathetically.

"Don't cry, poor Audrey," he said. "My t'roat isn't so vrezy bad."

Uncle Geoff was very kind.

"No," he said. "I don't think it'll be very bad. But you must take greatcare of him, Audrey. And I don't know how to do. I don't like your beingleft so much alone, and yet there's no one in the house fit to takecare of you."

"Hasn't Mrs. Partridge got a new nurse for us?" I asked.

"No," said Uncle Geoff, smiling a little. "She hasn't found one yet."

There came a sort of squeal from the corner of the room. We all started.It was Racey. He was playing as usual with his beloved horses, notseeming to pay any attention to what we were saying. But he wasattending all the time, and the squeal was a squeal of delight athearing that the new nurse was not coming.

"What is the matter, Racey?" I said.

"Her's not tumming," he shouted. "Her won't whip us."

"Who said anything about being whipped?" said Uncle Geoff.

We hesitated.

"I don't quite know," I said. "Mrs. Partridge said we should have a verystrict nurse, and I don't know how it was the boys thought she'd whipthem."

Uncle Geoff looked rather grave again.

"I must go," he said. "I will let Miss Goldy-hair,"--he smiled againwhen he said it--"I will let her know that I can't let Tom out to-dayand that his good little sister won't leave him;"--how kind I thoughtit of Uncle Geoff to say that!--"and I must do the best I can to find anice nurse for you--one that won't whip you, Racey."

"Must Tom go to bed?" I asked.

"No," said Uncle Geoff, "if he keeps warm and out of the draughts. Mrs.Partridge will come up to see him; but you needn't be afraid, Audrey,I'm not going to say anything about last night to her. You and I havemade an agreement, you know."

Mrs. Partridge did come up, and she was really very kind--much kinderthan she had been before. She was one of those people that get nicerwhen you're ill; and besides, Uncle Geoff had said something to her, I'msure, though I never knew exactly what. Any way she left off calling usnaughty and telling us what a trouble we were. But it was all thanks toMiss Goldy-hair, Tom and I said so to each other over and over again. Noone else could have put things right the way she had done.

Tom was very good and patient, though his throat was really pretty badand his head ached. Mrs. Partridge sent him some black currant tea todrink a little of every now and then, and Uncle Geoff sent Benjamin tothe chemist's with some doctor's writing on a paper and he brought backsome rather nasty medicine which poor Tom had to take every two hours.But though I did my very best to amuse him, and read him over and overagain all the stories I could find, it seemed a very long, cold, dullmorning, and we couldn't help thinking how different it was from what wehad hoped for--spending the day with Miss Goldy-hair, I mean.

"If only we hadn't gone out in the cold last night you'd have been quitewell to-day, Tom," I said sadly.

"Yes, but then we wouldn't have found Miss Goldy-hair," said Tom.

"I don't see that it's much good to have found her," said I. I wasrather dull and sorry about Tom, and I didn't know what more to do toamuse him. "I don't believe we'll see her for ever so long, and perhapsshe'll forget about us as she has such a lot of children she cares for."

"But they're _poor_ children," said Tom, "she can't like them as much asus. She said so."

"She didn't mean it that way," I said. "She'd be very angry if she'dheard you say that, as if poor children weren't as good as rich ones."

"But she _did_ say so," persisted Tom. "When I asked her if going to seethe poor children was as nice as if she had us always, she said no."

"Well, she meant it wasn't as nice as if she was mother and had herown children always. She didn't mean anything about because they werepoor. _I_ believe she likes poor children best. Lots of people do, andI'm sure we've lots of trouble too, though we're not poor. If we'd beenpoor like the ones in _Little Meg's Children_, or _Froggy's BrotherBen_, Miss Goldy-hair would have been here _ever_ so e

arly this morning,with blankets and coals, and milk, and bread and sugar--"

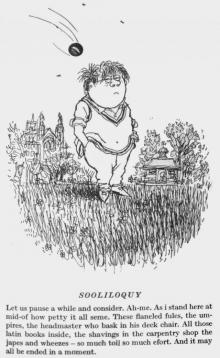

"And 'tawberry dam and delly and 'ponge cakes and olanges andeberysing," interrupted Racey, coming forward from his corner.

In walked Miss Goldy-hair herself!]

I had been "working myself up," as Pierson used to call it, and I wasfast persuading myself that Miss Goldy-hair was very unkind, and thatafter all we were poor deserted little creatures, but for all that Icouldn't help laughing at Racey breaking in with his list of what hethought the greatest delicacies. Tom laughed too-- I must say in someways Tom was a very good little boy in spite of his sore throat, andRacey was standing with his head on one side considering what more hewould wish for in Miss Goldy-hair's basket, when--_wasn't_ itfunny?--there came a little tap at the door, and almost before we couldsay "come in," it opened, and--oh, how delighted we were--in walked MissGoldy-hair herself!

She was smiling with pleasure at our surprise, and wonderful to say, shewas carrying a big, big basket, such a big basket that Tom, who hadvery nice manners for a boy, jumped up at once to help her with it, andin the nice way she had she let him think he was helping her a greatdeal, though really she kept all the weight of it herself, till betweenthem they got it landed safely on the table.

Racey danced forward in delight.

"Audrey, Audrey," he cried, "her _has_ got a basket, and her _has_ come.Her said she would."

Miss Goldy-hair stooped down to kiss his eager little face. Then sheturned to me and kissed me too, but I felt as if I hardly deserved it.

"Did you think I had forgotten you, Audrey?" she said.

I felt my cheeks get very red, but I didn't speak.

"Didn't you promise to trust me last night?" she said again.

"Yes, Miss Goldy-hair, but I didn't know that you'd come to see usbecause Tom was ill. You said you'd come to fetch us to have dinner andtea with you, but I didn't know you'd come when you heard Tom couldn'tgo out."

"Why, don't you need me all the more because you can't go out?" she saidbrightly. "I'm going to stay a good while with you, and I have broughtsome little things to please you."

She turned to the basket which Racey had never taken his eyes off. Weall stood round her, gazing eagerly. There were all sorts of things toplease us--oranges, and a few grapes, and actually a little shape ofjelly and some awfully nice funny biscuits. Then there were a few books,and two or three little dolls without any clothes on, and a littlepacket of pieces of silk and nice stuffs to dress them with, and a rollof beautiful coloured paper, and some canvas with patterns marked on it,and bright-coloured wools.

"I've brought you some things to amuse you," said Miss Goldy-hair, "forTom can't go out, and it's a very cold, wet day, not fit for Audrey orRacey to go out either. And as your tutor won't be coming as Tom's ill,it would be a very long day for you all alone, wouldn't it?"

Then she went on to explain to us what she meant us to do with thethings she had brought. Some of them were the same that the children shehad told us about had to amuse them when they were ill, and she let Tomand Racey choose a canvas pattern each, and helped them to begin workingthem with the pretty wools.

"How nice it would be to make something pretty to send to your motherfor Christmas! Wouldn't she be surprised?" she said; and Tom was sopleased at the thought that he set to work very hard and tried so muchthat he soon learnt to do cross-stitch quite well. Racey did a little ofhis too, but after a while he got tired of it and went back to hishorses, and we heard him "gee-up"-ing, and "gee-woh"-ing, and "standthere, will you"-ing in his corner just as usual.

"What a merry little fellow he is," said Miss Goldy-hair, "how well heamuses himself."

"Yes," I said, "he hasn't been near so dull as Tom and me. He was onlyfrightened for fear the new nurse should whip him. But Uncle Geoff haspromised she sha'n't, and so now Racey's quite happy and doesn't mindanything. I don't think he minds about mother going away now."

"He's such a little boy," said Miss Goldy-hair.

But I was a little mistaken about Racey. He thought of things more thanI knew.

Then Miss Goldy-hair helped me to begin dressing the little dolls. Theywere for a little ill girl who couldn't dress them for herself, as shehad to lie flat down all day and could hardly move at all because herback was weak somehow, but she was very fond of little dolls and likedto have them put round her where she could see them. I had never dressedsuch small ones before, and it was great fun, though rather difficult.But after I had worked at them for a good while Miss Goldy-hair toldboth Tom and me that we'd better leave off and go on with our work inthe afternoon.

"It's never a good plan to work at anything till you get quite tired,"she said. "It only makes you feel wearied and cross, and then you neverhave the same pleasure in the work again. Besides, it must be nearlyyour dinner-time, and I must be thinking of going home."

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories

An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car

Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car The Children of the Castle

The Children of the Castle The Magic Nuts

The Magic Nuts Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Silverthorns

Silverthorns The Third Miss St Quentin

The Third Miss St Quentin Christmas-Tree Land

Christmas-Tree Land Philippa

Philippa Jasper

Jasper The Little Old Portrait

The Little Old Portrait Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Us, An Old Fashioned Story

Us, An Old Fashioned Story The Constant Prince

The Constant Prince Blanche: A Story for Girls

Blanche: A Story for Girls The Cuckoo Clock

The Cuckoo Clock The Carved Lions

The Carved Lions Tell Me a Story

Tell Me a Story That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie

That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie Sweet Content

Sweet Content Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories

The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball

Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball Nurse Heatherdale's Story

Nurse Heatherdale's Story Adventures of Herr Baby

Adventures of Herr Baby Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver

Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories

Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy

Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy