- Home

- Mrs. Molesworth

Blanche: A Story for Girls Page 14

Blanche: A Story for Girls Read online

Page 14

India before I was grown up. She only remembers me as achild more or less. But now I can write to Sir Adam himself, and hewill be sure to ask some old friends to come to see us."

And that very day she did so.

But the result was not what she had hoped. A few thoroughly kind wordsfrom her old friend came in response in the course of a week or two,hoping to see her and her children on his return to England thefollowing spring, but evidently not "taking in" the Derwents' presentloneliness. "I hear from Amy Lilford that she has asked her tenants tolook after you a little," he said. "I don't know them personally, butyou will like to have the run of the old place again."

And Mrs Derwent could not make up her mind to trouble him further. "Menhate writing any letters that are not business ones," she said toBlanche. "We must just wait till he comes back in the spring, and makeourselves as happy as we can till then; though, of course, I hope somepeople will call on us as soon as we are settled. The Marths at EastModdersham could scarcely do less."

To some little extent her expectations were fulfilled. The wife of thevicar of Blissmore called. The vicar was a younger son of the importantEnneslie family, enjoying the living in his father's gift afterold-fashioned orthodox fashion, and Mrs Enneslie was a conscientious"caller" on all her husbands parishioners. She had perception enough todiscern the Derwents' refinement and superiority at a glance, but shewas a very busy woman, with experience enough to know that to beaccepted by the "County," much more than these qualities was demanded.And she contented herself with such kindly attentions to the strangersas lay in her own power. She did a little more. She spoke of them toher brother, the Pinnerton Green parson, who promised that his wifeshould look them up as soon as they came under his clerical wing.

"They seem nice girls," she said, with perhaps some kindly meantdiplomacy. "It would be good for them to do a little Sunday-schoolingor something of that kind."

So the weeks passed, bringing with them the exasperating delays whichevery one in the agonies of house changing thinks peculiar to one's owncase; and Christmas came and went before the Derwents could even name atime with any certainty for taking possession of their new home. It wasa dull Christmas. Not that, with their French experience, the youngpeople were accustomed to Yule-tide joviality; but they had heard somuch about it--had pictured to themselves the delights of an overflowingcountry-house, the glories of a real English Christmas, as their motherhad so often from their earliest years described it to them.

And the reality--Miss Halliday's best sitting-room, with some sprigs ofholly, a miniature (though far from badly made) plum-pudding, nopresents or felicitations except those they gave each other!

"Another of my illusions gone," said Stasy, with half-comical pathos,which drew forth a warning whisper from Blanche of "Don't, Stasy. Itworries mamma," and aloud the reminder:

"Everything will be quite different when we are in our own house, yousilly girl."

And when at last the own house did come, and the pleasant stage began ofmaking the rooms home-like and pretty with the old friends so longimmured in packing cases, and the new dainty trifles picked up inLondon, in spite of the fogs, for a short time they were all very busy,and perfectly happy--satisfied that the lonely half-homesick feeling hadonly been a passing experience.

"I am really glad not to have made new friends till now," said MrsDerwent. "It does look so different here, though we have been verycomfortable at Miss Halliday's, and she has been most good to us."

"Yes," Blanche agreed; "and I think we should make up our minds to _be_happy here, whether we know many nice people or not, mamma. The onlything I really care about is a little good companionship for Stasy."

"She must not make friends with any girls beneath her--as to that I amdetermined," said Mrs Derwent.

"Far better have none. Not that anything could make _her_ common, butit would be bad for her to feel herself the superior; and I can pictureher queening it over others, and then making fun of them and their homesand ways. She has such a sense of the ridiculous. No; Stasy needs tobe with those she can look up to. I am sure, Blanche, it is better notto think of her going to that day-school at Blissmore."

For Stasy was only sixteen, and the question of her studies was still aquestion. At Blissmore, under the shadow of the now important publicschool for boys, various minor institutions for girls were springing up,all, as might have been expected, of a rather mixed class, though theteaching in most was good.

And Stasy, for her part, would have thought it "great fun" to go toschool for a year or so.

The matter was compromised by arrangements being made for her havingprivate lessons at home on certain days of the week, and joining one ortwo classes at the best girls' school at Blissmore on others, to whichshe could be escorted by Aline when she took little Herty to hisday-school.

CHAPTER EIGHT.

OLD SCENES.

By March the Derwents felt quite at home in their new abode; in onesense, almost too much so. The excitement of settling had sobered down;the housekeeping arrangements were completed, and promising to worksmoothly. For Mrs Derwent had profited by her twenty years of Frenchlife in becoming a most capable and practical housewife, and beingnaturally quick and able to adapt herself, she soon mastered the littledifficulties consequent on the very different ideas as to materialquestions of her own and her adopted country.

So that, in point of fact, time was in danger of hanging rather heavilyon their hands; there was really so little to do!

Their peculiar position cut them off from many of the occupations withwhich most of us nowadays are only too heavily burdened. They had fewletters to write, for Frenchwomen are not great correspondents--in theprovinces, at least--and when the Derwents left Bordeaux, their oldfriends there extracted no promises of "writing very often--very, veryoften."

"Notes," of course, which in London seem to use up hours of each day,there was never any occasion for. They had no calls to pay, beyond arare one at the vicarage; no visitors to receive. For the PinnertonGreen folk had not followed suit, as the Derwents had feared, after MrsBurgess's invasion. Nothing had been heard of Mrs Wandle, and--probablythrough some breath of the great Lady Harriot Dunstan's visit, and MrsEnneslie's introduction of the new-comers to her relations at PinnertonVicarage--the immediate neighbours had held back: the "butchers andbakers and candlestick-makers" had left them in peace. Mrs Burgesshaving been called away to a sick sister or niece early in the winter,and not yet having returned, even the excitement of watching her tacticshad been wanting.

In short, the Derwents, socially speaking, were very distinctly in theposition, to use a homely old saying, of "falling between two stools."

And though Stasy was the least to be pitied, for her lessons kept herpretty fairly busy, and she managed to find food for amusement andmaterial for mimicry among her class companions--some of whom, too, shereally liked--at Mrs Maxton's school, she was the readiest to grumble.

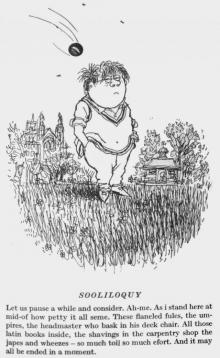

"What is the use of making the house pretty when there is no one to seeit?" she said to her sister one afternoon, when the two had beenemploying themselves in hunting for early violets and primroses in thewoods, with which to adorn the library, their favourite sitting-room.There were not many of these spring treasures as yet, for the season wasa late one, but they were laden with other spoil, as lovely in its way--great trails of ivy and bunches of withered or half-withered leaves ofevery shade, from golden brown to crimson, which in sheltered nooks werestill to be found arrested in their beautiful decay.

"What is the use of making the house pretty when there is never any oneto see it?" Stasy repeated, as she flicked away an unsightly twig fromthe quaint posy she was carrying, for Blanche had not at once replied.

"There is always use in making one's home as pretty as possible. Thereare ourselves to see it, and the--the thing itself," replied Blanche alittle vaguely.

"What do you mean by the thing itself?" Stasy demanded.

"The being pretty, or the trying to be--the aiming at

beauty, I suppose,I mean," said Blanche. "Can't you imagine a painter giving years to abeautiful picture, even though he knew no one would ever see it buthimself? or a musician composing music no one would ever hear?"

"No," said Stasy, "I can't. That sort of thing is flights above me,Blanchie. I like human beings about me--lots of them; they generallyinterest me, and often amuse me. I like a good many, and I am quiteready to love _some_. I want sympathy and life, and--and--well,perhaps, a little admiration. And I do think it's too horribly dullhere; at least, I'm afraid it's going to be. I would rather leave offbeing at all grand, and get some fun out of the Wandles, and theBeltons, and all the rest of them."

"Mamma is

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories

An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car

Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car The Children of the Castle

The Children of the Castle The Magic Nuts

The Magic Nuts Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Silverthorns

Silverthorns The Third Miss St Quentin

The Third Miss St Quentin Christmas-Tree Land

Christmas-Tree Land Philippa

Philippa Jasper

Jasper The Little Old Portrait

The Little Old Portrait Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Us, An Old Fashioned Story

Us, An Old Fashioned Story The Constant Prince

The Constant Prince Blanche: A Story for Girls

Blanche: A Story for Girls The Cuckoo Clock

The Cuckoo Clock The Carved Lions

The Carved Lions Tell Me a Story

Tell Me a Story That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie

That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie Sweet Content

Sweet Content Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories

The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball

Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball Nurse Heatherdale's Story

Nurse Heatherdale's Story Adventures of Herr Baby

Adventures of Herr Baby Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver

Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories

Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy

Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy