- Home

Page 2

Page 2

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories

An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

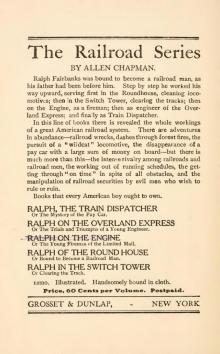

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car

Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car The Children of the Castle

The Children of the Castle The Magic Nuts

The Magic Nuts Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Silverthorns

Silverthorns The Third Miss St Quentin

The Third Miss St Quentin Christmas-Tree Land

Christmas-Tree Land Philippa

Philippa Jasper

Jasper The Little Old Portrait

The Little Old Portrait Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Us, An Old Fashioned Story

Us, An Old Fashioned Story The Constant Prince

The Constant Prince Blanche: A Story for Girls

Blanche: A Story for Girls The Cuckoo Clock

The Cuckoo Clock The Carved Lions

The Carved Lions Tell Me a Story

Tell Me a Story That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie

That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie Sweet Content

Sweet Content Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories

The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball

Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball Nurse Heatherdale's Story

Nurse Heatherdale's Story Adventures of Herr Baby

Adventures of Herr Baby Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver

Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories

Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy

Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy