- Home

- Mrs. Molesworth

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Page 4

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Read online

Page 4

and a very tiny, weeny bit frightened. Everything seemed"funny" this birthday morning. She almost felt as if she was dreaming.

"Why is mamma's room all dark?" she said again. "Is her asleep?"

"I'm not sure, dear. Wait here a minute and I'll see," and her fatherwent into the next room, closing the door a little after him.

Mary and her brothers stood looking at each other. What was going tohappen?

"It's to be a surprise, I s'pose," said Artie.

"It's the guesses, _I_ say," said Leigh.

"It's a birfday present for me. Papa said so," said Mary.

"We're speaking like the three bears," said Artie laughing. "Let's goon doing it. It's rather fun. You say something, Leigh--say`somebody's been in my bed'--that'll do quite well. Say it verygrowlily."

"Somebody's been in my bed," said Leigh, as growlily as he could. Leighwas a very good-natured boy, you see.

"Now, it's my turn," said Artie, and he tried to make his voice into akind of gruff squeak that he thought would do for the mamma bear'stalking. "Somebody's been in _my_ bed," he said. "Come along, Mary,it's you now."

Mary was laughing by this time.

"Somebody," she began in a queer little peepy tone, "somebody's--" butsuddenly a voice from the other side of the door made them all jump.

"My dear three bears," it said--it was papa, of course, "be so good asto shut your eyes _tight_ till I tell you to open them, and then Marycan finish." They did shut their eyes--they heard papa come into theroom and cross over to the corner which they had not looked at. Thenthere was a little rustling--then he called out:

"All right. Open your eyes. Now, Mary, Tiny Bear, fire away.Somebody's lying--"

"In my bed," said Mary, as she opened her eyes, thinking to herself how_very_ funny papa was.

But when her eyes were quite open she did stare. For there he wasbeckoning to her from the corner where he was standing beside a dearlittle bed, all white lace or muslin--Mary called all sorts of stufflike that "lace"--and pink ribbons.

"Oh," said Mary, running across the room, "that's _my_ bed. Mammashowed it me one day. It were my bed when I was a little girl."

"Of course, it's your bed," said her father. "I told you to be TinyBear and say, `somebody's lying in my bed.' Somebody _is_ lying in yourbed. Look and see."

Mary raised herself up on her tiptoes and peeped in. On the soft whitepillow a little head was resting--a little head with dark fluffy curlsall over it--Mary could not see all the curls, for there was a flannelshawl drawn round the little head, but she could see the face and thecurls above the forehead. "It," this wonderful new doll, seemed to beasleep--its eyes were shut, and its mouth was a tiny bit open, and itwas breathing very softly. It had a dear little button of a nose, andit was rather pink all over. It looked very cosy and peaceful, andthere seemed a sweet sort of lavendery scent all about the bed and thepretty new flannel blankets and the embroidered coverlet. That _was_pretty--white cashmere worked with tiny rosebuds. Mary rememberedseeing her mamma working at it, and it was lined with pale pink silk.But just then, though Mary saw all these things and noticed them, yet,in another way, she did not see them. For all her real seeing andnoticing went to the living thing in this dear little nest, the little,soft, sleeping, breathing face, that she gazed at as if she could neverleave off. And behind her, gazing too, though Mary had the best place,of course, as it was her birthday and she was a girl--behind her stoodher brothers. For a few seconds, which seemed longer to the children,there was perfect silence in the room. It was a strange wonderfulsilence. Mary never forgot it.

Her breath came fast, her heart seemed to beat in a different way, herlittle face, which was generally rather pale, grew flushed. And then atlast she turned to her father who was waiting quietly. He did not wantto interrupt them. "Like as if we were saying our prayers, wasn't it?"Artie said afterwards. But when Mary turned she felt that he had beenwatching them all the time, and there was a _very_ nice smile on hisface.

"Papa," she said. She seemed as if she could not get out another word,"papa--is it?"

"Yes, darling," he replied, "it is. It's a baby sister. Isn't that thenicest present you ever had?"

Then there came back to Mary what she had often said about "not wantinga baby sister," and she could scarcely believe she had ever felt likethat. She was sorry to remember she had said it, only she knew she hadnot understood about it.

"I never thought her would be so pretty," she said. "I never thoughther would be so sweet. Oh papa, her is a _lubly_ birfday present! Whenher wakes up, mayn't I kiss her?"

"Of course you may, and hold her in your arms if you are very careful,"said her father, looking very pleased. He had been very anxious forMary to love the baby a great deal, for sometimes "next-to-the-baby"children are rather jealous and cross at being no longer the pet and theyoungest. It was a very good thing he and her mamma agreed that thebaby had come as a birthday present to Mary.

The idea of holding her in her own arms was so delightful that again fora moment or two Mary felt as if she could not speak.

"And what do you two fellows think of your new sister?" said papa,turning to the boys. Leigh leant over the cradle and peered in veryearnestly.

"She's something like," he said slowly, "something like those very tinylittle ducklings," and seeing a smile on his father's face he went on toexplain, though he grew rather red, "I don't know what makes me thinkthat. She looks so soft and cosy, I suppose. You know the littleducklings, papa? They're like balls of fluffy down."

"I don't think she's a bit like them," said Artie, who in his turn hadbeen having a good examination of the baby. "I think she's more like avery little monkey. Do you remember that tiny monkey with a pink face,that sat on the organ in the street at grandmamma's one day, Leigh? It_was_ like her."

He spoke quite gravely. He had admired the monkey very much. He didnot at all mean that the new baby was not pretty, and his father's smilegrew rather comical.

"See how she scroozles up her face," he went on; "she's _just_ like themonkey now. It was a very nice monkey, you know, papa."

But Mary was not pleased. She had never seen a monkey, but there was apicture of one for the letter "M" in what she called her "animal book,"and she did not think it pretty at all.

"No," she said, "no, Artie, her's not a' inch like a monkey. Her's_booful_, just booful, and monkeys isn't."

Then suddenly she gave a little cry.

"Oh papa, dear, do look," she called out, "her's openin' her eyes. Inever 'amembered her could open her eyes," and Mary nearly danced withdelight.

Yes indeed, Miss Baby was opening her eyes and more than her eyes--herlittle round mouth opened too, and she began to cry--quite loud!

Mary had heard babies cry before now, of course, but somehow everythingabout _this_ baby was too wonderful. She did not seem at all like thebabies Mary saw sometimes when she was out walking; she was like herselfand not anything else.

Mary's face grew red again when she heard the baby cry.

"Oh papa, dear," she said. "Has her hurt herself?"

"No, no, she's all right," said papa. But all the same he did not takebaby out of her cot--papas are very fond of their babies of course, butI do not think they like them _quite_ so much when they cry--instead ofthat, he turned towards the door leading into the next room.

"Nurse," he said in a low voice, but nurse heard him.

"Yes, sir," said a voice, in reply, and then came another surprise forMary. The person who came quickly into the room was not "nurse" at all,but somebody quite different, though she had a nice face and was veryneatly dressed. Who could she be? The world did seem _very_ upsidedown this birthday morning to Mary!

"Nurse," she repeated to her father, with a very puzzled look.

"Yes, dear," said the stranger, "I'm come to be baby's nurse. You seeshe needs so much taking care of just now while she's still so verylittle--your nurse wouldn't have time to do it all."

&

nbsp; "No," said Mary, "I think it's a good plan," and she gave a little sighof satisfaction. She loved the baby dearly already and she would havebeen quite ready to give her anything--any of her toys or pretty things,if they would have pleased her--but still she did feel it would havebeen rather hard for _her_ nurse to be so busy all day that she couldnot take care of Artie and her as usual.

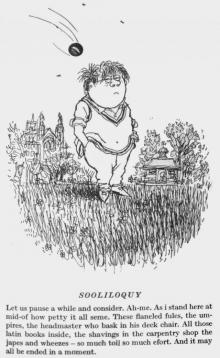

The strange nurse smiled. Mary was what people call an "old-fashioned"child, and one of her funny expressions was saying anything that sheliked was "a good plan." She stood staring with all her eyes as thenurse cleverly lifted baby out of the cot and laid her on her knee in acomfortable way, so that she left off crying. But her eyes were stillopen, and Mary came close to look at them.

"Is her going to stay awake now?" she said. "Perhaps she will, for alittle while," said the nurse. "But such very tiny babies like to sleepa great deal."

Mary stood quite still. She felt as if she could stay there all dayjust looking at the baby--every moment she found out some new wonderabout her.

"Her's got ears," she said at last.

"Of course she has," said the strange nurse. "You wouldn't like her tobe deaf?"

"Baby," said Mary, but baby took no notice.

"Her _it_ deaf," she went on, looking very disappointed. "Her doesn'tlook at me when I call her."

"No, my dear," said the nurse. "She hasn't learnt yet to understand.It will take a good while. You will have to be very patient. Littlebabies have a great, great deal to learn when they first come into thisworld. Just think what a great many things you have learnt yourselfsince you were a baby, Miss Mary."

Mary looked at her. She had never thought of this.

"I wasn't never so little, was I?" she said.

"Yes, quite as little. And you couldn't speak, or stand, or walk, or doanything except what this little baby does."

This was very strange to think of. Mary thought about it for a momentor two without speaking. Then she was just going to ask some morequestions, when she heard her father's voice.

"Mary," he said, "mamma is awake and you may come in and get a birthdaykiss. Leigh and Artie are waiting for you to have the first kiss asyou're the queen of the day."

"I'd like there to be two queens," said Mary, as she trotted across toher father. "'Cos of baby coming on my birfday. When will her have abirfday of hers own?" she went on, stopping short on her way when thisthought came into her head.

Her father laughed as he picked her up.

"I'm afraid you'll have to wait a whole year for that," he said. "Nextyear, if all's well, your birthday and baby's will come together."

"Oh, that will be nice," said Mary, but then for a minute or two sheforgot all about baby, as her father lifted her on to her mother's bedto get the birthday kiss waiting for her.

"My pet," said her mother, "are you pleased with your presents, and areyou having a happy day?" Mary put up her little hand and stroked hermother's forehead, on which some little curls of pretty brown werefalling.

"Mamma dear," she said, "your hair isn't very tidy. Shall I call Larkinto brush it smoove?" and she began to scramble off the bed to go tofetch the maid.

"What a little fidget you are," said her mother. "Never mind about myhair. I want you to tell me what you think of your little sister."

"I think her _sweet_," said Mary. "And her curls is somefin like yours,mamma. But Leigh says hers like little ducks, and Artie says hers likea pink monkey."

Mamma began to laugh at this, quite loud. But just then the nurse puther head in at the door.

"Baby's opening her eyes so wide, Miss Mary," she said. "Do come andlook at her, and you, Master Leigh and Master Artie too. You shall comeand see your mamma again in the afternoon."

So they all three went back into the other room to have another look atbaby.

"I say, children," called their father after them. "We've got to fixwhat baby's to be called. It'll take a lot of thinking about, so youmust set your wits to work, and tell me to-morrow what name you likebest."

CHAPTER FOUR.

BABIES.

There was plenty to think of all that day. Mary's little head had neverbeen so full, and before bedtime came she began to feel quite sleepy.

It had been a very happy day, even though everything seemed ratherstrange. Their father would have liked to stay with them, but he wasobliged to go away. Nurse--I mean Artie's and Mary's own nurse--was_very_ good to them, and so were cook and all the other servants. Thebirthday dinner was just what Mary liked--roast chicken and bread-sauceand little squirly rolls of bacon, and a sponge-cake pudding withstrawberry jam. And there was a very nice tea, too; the only pity wasthat baby could not have any of the good things, because, as nurseexplained, she had no teeth.

"She'll have some by next birthday, won't she?" asked Leigh.

"I hope so, poor dear," said nurse, "though she'll scarcely be able toeat roast chicken by then."

"Why do you say `poor dear'?" asked Leigh.

"Because their teeth coming often hurts babies a good deal," said nurse.

"It would be much better if they were all ready," said Leigh. "I don'tsee why they shouldn't be. Baby's got hands and eyes and everythingelse--why shouldn't she have teeth?"

"I'm sure I can't say, Master Leigh," nurse answered. "There's manythings we can't explain."

Mary opened her mouth wide and began tugging at her own little whiteteeth.

"Them doesn't hurt me," she said.

"Ah but they did, Miss Mary," said nurse. "Many a night you couldn'tsleep for crying with the pain of them, but you can't remember it."

"It's very funny," said Mary.

"What's funny?" asked Leigh.

"About 'amembering," answered Mary, and a puzzled look came into herface. "Can you 'amember when you was a tiny baby, nurse?"

"No, my dear, nobody can," said nurse. "But don't worry yourself aboutunderstanding things of that kind."

"There's somefin in my head now that I can't 'amember," said Mary,"somefin papa said. It's that that's teasing me, nurse. I don't liketo not 'amember what papa said."

"You must ask him to-morrow, dearie," nurse answered. "You'll giveyourself a headache if you go on trying too hard to remember."

"Isn't it _funny_ how things go out of our minds like that?" said Leigh."I'll tell you what I think it is. I think our minds are likecupboards or chests of drawers, and some of the things get poked veryfar back so that we can't get at them when we want them. You see thenewest things are at the front, that's how we can remember things thathave just happened and not things long ago."

"No," said Artie, "'tisn't quite like that, Leigh. For I can rememberwhat we had for dinner on my birthday, and that was very long ago,before last winter, much better than what we had for dinner one day lastweek."

"I can tell you how that is," said nurse, "what you had for dinner onyour birthday made a mark on your mind because it was your birthday.Everything makes marks on our minds, I suppose, but some go deeper thanothers. That's how it's always seemed to me about remembering andforgetting. And if there's any name I want to remember very much I sayit out loud to myself two or three times, and that seems to press itinto my mind. Dear, dear, how well I remember doing that way at schoolwhen I was a little girl. There was the kings and queens, do what Iwould, I couldn't remember how their names came, till I got that way ofsaying two or three together, like `William and Mary, Anne, George theFirst,' over and over."

The children listened with great interest to nurse's recollections, theboys especially, that is to say; the talk was rather too difficult forMary to understand. But her face looked very grave; she seemed to belistening to what nurse said, and yet thinking of something behind it.All at once her eyes grew bright and a smile broke out like a ray ofsunshine.

"I 'amember," she said joyfully. "Nursie said her couldn't 'amembernames. It was names papa said. He said us was to fink of a name forbaby."

"Oh, is that what you've been fussing about?" s

aid Leigh. "I could havetold you that long ago. _I've_ fixed what I want her to be called.I've thought of a _very_ pretty name."

Mary looked rather sorry.

"I can't fink of any names," she said; "I can only fink of `Mary.'Can't her be called `Mary,' 'cos it's my birfday?"

Leigh and Artie both began to laugh.

"What a silly girl you are," said Leigh; "how could you have two peoplein one family with the same name? Whenever we called `Mary,' you'dnever know if it was you or the baby we meant."

"You could say `baby Mary,'" said

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift

The Iron Boys as Foremen; or, Heading the Diamond Drill Shift An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories

An Enchanted Garden: Fairy Stories Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls

Grandmother Dear: A Book for Boys and Girls Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car

Ralph, the Train Dispatcher; Or, The Mystery of the Pay Car The Children of the Castle

The Children of the Castle The Magic Nuts

The Magic Nuts Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Silverthorns

Silverthorns The Third Miss St Quentin

The Third Miss St Quentin Christmas-Tree Land

Christmas-Tree Land Philippa

Philippa Jasper

Jasper The Little Old Portrait

The Little Old Portrait Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children

Mary: A Nursery Story for Very Little Children Us, An Old Fashioned Story

Us, An Old Fashioned Story The Constant Prince

The Constant Prince Blanche: A Story for Girls

Blanche: A Story for Girls The Cuckoo Clock

The Cuckoo Clock The Carved Lions

The Carved Lions Tell Me a Story

Tell Me a Story That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie

That Girl in Black; and, Bronzie Sweet Content

Sweet Content Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children

Boys and I: A Child's Story for Children The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories

The Man with the Pan-Pipes, and Other Stories Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball

Bert Wilson's Fadeaway Ball Nurse Heatherdale's Story

Nurse Heatherdale's Story Adventures of Herr Baby

Adventures of Herr Baby Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver

Shaggycoat: The Biography of a Beaver Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories

Adventures of Prince Lazybones, and Other Stories Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy

Adventures of Piang the Moro Jungle Boy